Middle-aged anger gets trapped. It collects. It pools. It gets confused.

Whenever I feel angry, it’s worth reminding myself that I am forty two years old. Any anger I’ve felt towards my parents over the past few months has resonated with bellowing, shimmering, abandoned-airplane-hangar acoustics. Middle-aged anger gets trapped. It collects. It pools. It gets confused. Generally, it wants less help than young anger wants. Generally, it is more willing to ask for what it wants. Middle-aged anger hangs around and waits for someone to need it. It takes breaks to get the kids to school. Young anger can be held at bay with a couple of beers or an excellent sandwich. Middle-aged anger is less easily warded off. It stares at you while you watch it eat your sandwich. It stares at you while you watch it pour your beer out on the ground.

The anger I feel because my parents “missed” my autism is that middle-aged kind. And I put quotes around “missed” because in hindsight I’m not sure it was quite the right word.

Did my parents miss this? Did my teachers miss this? Did anyone miss this?

I need to do better than “miss” to get at the heart of the question. I need to do better than “miss” to be fair to those I’m putting under scrutiny.

Perhaps predictably, I’ve made a little checklist:

Is it reasonable to expect _______ to have noticed that I had autism?

Is it reasonable to expect _______ to have noticed that something was up with me?

Is it reasonable to expect _______ to have done something if they knew that something was up with me?

Let’s fill in the blanks with “my parents” and see what happens.

Series Note

This essay is part of an ongoing series in which I explore each of the feelings that washed over me when I received my diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) at forty two.

My parents died when I was relatively young—my father when I was seventeen and my mother when I was twenty three. That’s a whole story unto itself. Two whole stories, really. I’ve spent more of my life without a father than with one. In just a few years, I’ll have spent more of my life without a mother than with one. Their deaths sit right in the middle of my life. Their deaths color everything. The pigment dilutes over time, but all of the thoughts and memories I have—including those formed after their deaths and those yet to be formed—are washed over with a coat of Dead Parents White.

There’s no avoiding it. If I ever decide to really write about the death of my parents, it won’t be as a sidebar in an essay about something else. I bring it up here partially to give context, but primarily to be fair to them. I can’t ask them questions about how they perceived my behavior as a child. I can’t ask them what they wish they’d done differently and what they would stand by. I’ll do my best to give them the benefit of the doubt and to try to see myself through their eyes. I’ll try, but I have to admit at the start that I don’t really believe it’s possible.

That said…

Is it reasonable to expect my mom to have noticed that I had autism?

Probably not.

It was the eighties in America, which is to say, it was the fifties in America but with the following modifiers:

The Equal Pay Act of 1963

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Voting Act of 1965

The Civil Rights Act of 1968

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973

The Education for All Handicapped Children (EHA) Act of 1975

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978

Interestingly, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) wouldn’t be signed into law until 1990 when I was seven going on eight—smack dab in the middle of my childhood. That same year, the EHA was reauthorized and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and expanded with further initiatives.

I was a kid with special needs. That’s accurate. I just didn’t know it at the time.

My mom was a teacher. When I was little, she taught third grade at my elementary school, but before I was born, she’d spent most of the seventies working with students that most people would have called “handicapped” at the time. I remember my mom telling me that she’d worked with students with Down syndrome, but beyond that, I don’t know the exact makeup of the classes she taught. I don’t know which disabilities she would have had firsthand experience with, but in the seventies, it wasn’t uncommon for a special education classroom to include children with quite varied cognitive and physical abilities. A special education teacher might be working with a student with cerebral palsy, a student with Down syndrome, and a student with autism in the same physical space, regardless of how their particular physical, emotional, and educational needs did and did not align with one another. This was considered an improvement over the sixties when it was still common for “handicapped” children to be excluded from the educational system. It was still common for them to be institutionalized.

I know that my mom was proud of her early work in special education. She might have been stuck with the pedagogy of the time, but I remember her being sincerely sensitive to students at my own school. I remember her advocating for them, even in small ways. If someone said something offhanded that she felt was disrespectful, she would speak up. I remember her using the phrase “special needs”. She wanted my brother and me to be respectful of people with special needs. I think that term has aged better than many. It’s plain, it’s broad, and because it’s plain and broad, it’s almost always accurate. I was a kid with special needs. That’s accurate. I just didn’t know it at the time.

Eventually, the word “special” would become a pejorative, just like every other well-intentioned word that works until it doesn’t. The nineties must have been particularly hard for my mom in this regard—having to hear her own kid (me) and all of his adolescent, butthead friends throw around the “R” word like it was no big deal. I wince thinking about that now. I feel terrible knowing that at that age I prioritized being edgy for the sake of acceptance over being kind for the sake of decency. I knew better. My mom had taught me better—my dad had too. Using the “R” word and similar pejoratives was a monstrous thing to do. So, yes, I wince thinking about that now. But my mom must have winced all the time watching the world punch down on the kids she was trying to help. In spite of her shortcomings (some of which will come up later), she was principled in this way. She had real empathy. She put it to practical use. She had a real love for the underdog. She was quick to roll up her sleeves and actually help.

That was a bit of a digression, but I’m glad to have taken a moment to present my mom as a full and actual human being with a story of her own. It’s important to do, and I think it’s an easy thing to gloss over, especially if I’m working my way through a checklist. That said, I do want to get back to specifics and try to see the analysis through.

Over the course of her career, would my mom have encountered children with autism? Almost certainly. Would I have reminded her of them in any way? Probably not. The diagnosis I received this year—Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) level 1—didn’t exist as a diagnosis during my mother’s lifetime. In 2013, a spectrum of disorders were grouped together in the DSM-5 and reorganized as ASD levels 1, 2, and 3 in an attempt to acknowledge their common traits and, from a diagnostic standpoint, to more meaningfully differentiate the degree to which ASD impacts a given person’s abilities and autonomy.

If I had been diagnosed in the eighties with anything at all to do with what we now understand as ASD, it would have been Asperger syndrome. Would my mom have worked with children with that diagnosis? Would she have known it when she saw it? That, I honestly don’t know.

Given what I do know about my mom and about the world as it was during my childhood, I don’t believe I can fairly say that she “missed” my autism. Mom is in the clear on this one. And Dad? My dad had zero professional experience with special needs kids, so he’s in the clear too. So far, I have nothing to be angry with my parents about.

Is it reasonable to expect either of my parents to have noticed that something was up with me?

The answer for both of my parents—equally—is: Yes, absolutely.

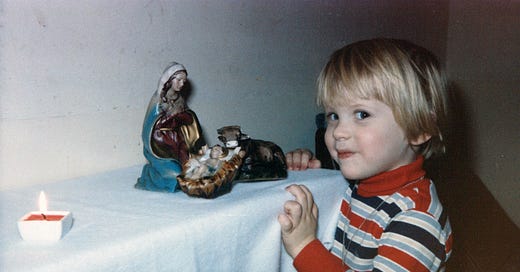

They saw me have emotional meltdowns in situations that didn’t seem to bother other kids. They saw my extreme sensitivity—my odd physical and emotional responses to touch and sound. They saw me fidget like hell when I was supposed to be kneeling in the pew. They knew that I couldn’t sit still during Sunday Mass if my life depended on it. They knew that my failure to memorize the Hail Mary week after week had sent me into a spiral of shame and panic that I really never recovered from (if recovery in this circumstance includes “became Catholic” and “learned the words to the Hail Mary” as criteria).

I suggest that my categorization as gifted was both fortunate and unfortunate not because it was a bad experience but because it may have given my parents the false impression that I was fine—and not merely fine but thriving.

Fortunately and unfortunately, what they also saw during my elementary school years was, “Your mostly happy kid, who doesn’t seem to have too much difficulty making and keeping friends here at the public elementary school, is gifted! Congratulations!”

Privilege check: Many students don’t have access to gifted programs in their schools. This is especially true for people of color. This was true when I was a kid. It remains true.

That said, I loved my gifted education classes. They felt safe and joyful. They engaged me. I had no fear that I would be picked on while I was there. Those teachers may have fallen short of recognizing that I had a disability, but they certainly recognized my differences. I remain grateful for those classes and for the wonderful people who taught them. Good job, Mrs. Overton.

I suggest that my categorization as gifted was both fortunate and unfortunate not because it was a bad experience but because it may have given my parents the false impression that I was fine—and not merely fine but thriving. Throughout my elementary school years, that would have been a pretty fair assessment in the context of the classroom. I was mostly fine and sometimes thriving.

But… In the Cub Scouts? At church? During CCD classes? In anything that involved being on a team? In those situations, I was not mostly fine and I was certainly not thriving. Those activities didn’t depend upon my uncanny ability to do well on tests without bothering to do homework. They didn’t depend upon my ability to do tangrams very quickly. They depended upon my ability to socialize well. They also depended upon my ability to take a certain amount of bullshit at face value and to not ask too many questions. I don’t have research to support what I’m about to say, but the unified act of eating shit and saying thank you is something I find that allistic people do much better autistic people. As such, those things were very hard for me. They were emotionally very difficult—nerve fraying. They still are.

This far along in my analysis, I can forgive my parents. I can give them a pass for not intervening in some way or for not researching a name for whatever I was or had because here is what they probably thought at the time: Paul is a bright, funny, moderately weird kid who is sensitive and hates church and can’t sit still and is maybe not cut out for team sports, but we love him and he seems happy most of the time and he has friends who he likes to play with after school and he’s in the gifted and talented program, so he’s probably fine. Right?

In other words, they thought I was a kid. A good kid. And kids are weird. Even good ones. I have kids. I understand this.

My parents must have thought: Every kid is different, and, all things considered, this one is doing pretty well. Fair enough.

Is it reasonable to expect either of my parents to have done something knowing that something was up with me?

Given the above and just the above? No, I don’t think it would be reasonable to have expected them to have intervened in some way. In keeping, I’ll give them another, final pass.

But the above is only true up to a certain point in time.

That point in time is when I was in seventh grade.

When I was in seventh grade, demanding to stay home from school “sick” because I just couldn’t imagine facing anyone… When I was in seventh grade, crying night after night because I was paralyzed by a stack of homework that had piled up... When I was in seventh grade, getting my first shitty grades... When I was in seventh grade, realizing just how important fitting in would be from then on and that I wasn’t very good at it… When I was in seventh grade, locking myself in the bathroom with a pair of scissors, crying for hours and refusing to come out…

Here, this post could go in a very different direction. But this is what I’ll say for now: I think it would have been clear to any parent—even parents in the eighties—that I was severely depressed, riddled with anxiety, unable to get a good night’s sleep, bullied routinely, and struggling greatly with school when social expertise, self-organization, and prolonged focus had all become basic requirements at roughly the same moment.

I learned as an adult—and only very recently—that depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and ADHD are frequent comorbidities with ASD. Over the years, I have been diagnosed with all of those things. ASD and ADHD were the last two to fall into place for me.

My mom’s solution was to helicopter, pave everything over, and get by. My dad’s solution was to do whatever it was that my dad was doing.

So, at this point, why am I stressing all this “not ASD” stuff? Because while it isn’t fair of me to be angry at my parents for “missing my ASD”, it is entirely reasonable to expect them to have done something once it became abundantly clear that something very serious was going on with my mental health—something beyond my control that was impacting my performance at school and was brewing depression and self-loathing.

This wasn’t the seventh-grade blues. It didn’t get better. I struggled with all of the above on and off all the way through graduate school, several years after both of my parents had passed away. I still struggle with them. My parents never took me to therapy. They never worked with the school to get me into counseling or to connect me with other available services. They never looked into testing for ADHD (something that almost certainly would have been on their radar). They never looked into other learning differences that might have explained my seemingly sudden paralysis over my schoolwork and my social life. My mom’s solution was to helicopter, pave everything over, and get by. My dad’s solution was to do whatever it was that my dad was doing.

Important aside: It really sucks that so much of this essay is focused on my mom. My mom, the one who made tough choices and took action. My mom, the one who was always there for the hard stuff.

The reward for a mom taking on the responsibility of her child’s schooling and most difficult emotional issues is that her enormous backlog of decisions made will be relatively easy to criticize at length when the grown child decides to audit.

This is one of patriarchy’s quaint little traps. Moms are expected to be the ones focused on and responsible for the emotional well-being of children. They’re expected to handle the nitty gritty of school i.e. difficult conversations with teachers and faculty. A mom can do all the emotional heavy lifting. She can take all the parent-teacher calls. She can always be the person on the other side of the bathroom door when her kid is threatening self harm.

She can do all of those things well or do them poorly. Ultimately, the paradigm has rendered her the parent with the paper trail. She did this wrong. She did that wrong. Never mind that the dad was… doing whatever the fuck the dad was doing. Dad shows up for the winter concert and he’s father of the year. The reward for a mom taking on the responsibility of her child’s schooling and most difficult emotional issues is that her enormous backlog of decisions made will be relatively easy to criticize at length when the grown child decides to audit.

Yet there are only so many ways you can say, “The father did not participate.”

Let me be clear then. When my mom swept my learning and emotional difficulties under the rug, that was bad. When my dad opted out of ever having to make those calls, that was worse. The father did not participate. End of aside.

Where were we? Right! My mom’s solution was to helicopter, pave everything over, and get by. My dad’s solution was to do whatever it was that my dad was doing. The family focus—whatever the underlying dynamic—was on everything seeming fine.

Which, for the most part, from the outside, I suppose it did. It must have seemed mostly fine.

Bullshit and wisdom exist on a spectrum.

It’s tempting to give my parents one final pass. Maybe they were just trying to protect me. Maybe society wasn’t advanced enough for them to be free of the old wisdom that “different” is often code for “shameful” and that it’s better to suffer in hiding than to seek help and risk becoming a target. Whether or not this wisdom has any merit is, of course, a matter of opinion. Bullshit is also a matter of opinion. Bullshit and wisdom exist on a spectrum.

I’ll go ahead and say that at present I see the “maybe they were just trying to protect you” defense as bullshit. This is where I wish I could really do my parents the service of letting them speak for themselves. They might have something to tell me that would turn my perception upside down. Perhaps they did ask the school counselors about my differences and I was none the wiser. Perhaps someone with expertise told them not to worry about it because I was “high functioning”. As it is, I can only conjecture.

They weren’t just protecting themselves from short circuit—they were leaving me to make sense of all of the pain I was going through on my own.

It may be cynical of me, but my best guess is that it was just too much for them. Even when my behavior started to frighten them, even when they must have been worried for my safety, it must have been overwhelming to think that their kid might be “special” and that they might have to get me special help and that they then would have to find some way to say as much—out loud—to their peers. To them, that must have felt like broadcasting that they were bad parents. If I take all of that and layer it on top of all of the other difficulties they were dealing with, it’s easy for me to sympathize with them. Paradoxically, one of the great stressors in their lives that must have made it all the more difficult to acknowledge that they might need to seek out professional help to get to the bottom of my suffering… was me. Having a child with all of the issues I’ve described is incredibly difficult. It takes a toll.

It feels compulsory to say, “They were doing the best they could,” but of course things are usually more complicated than that.

I’ve put my head in the sand many times in my life because it felt like the only safe thing I could manage at the time. I understand the impulse as a measure of self-protection. But in ignoring or explaining away their child’s mental health issues, my parents were putting my head in the sand. They weren’t just protecting themselves from short circuit—they were leaving me to make sense of all of the pain I was going through on my own. The implication of not acknowledging that I might have had a condition with a name that could have explained my behavior and my difficulties was that my behavior and my difficulties were my fault—something that I needed to buck up and fix rather than an inherent difference—a disability—that could be aided with professional intervention. The best I can say of putting your child’s head in the sand is that it is a kind of generational tragedy—not something to necessarily blame my parents or their parents for, but certainly not something I need to be handing out passes or medals for.

Did my parents “miss” my ASD? Not in so many words. But in avoiding addressing every other painfully obvious issue I had in my youth—even in actively hiding some of the worst of those issues—they also made it nearly impossible for anyone else to catch my ASD. For that reason, if for no other reason, I have an old, exhausted, electric anger that can’t stop hearing its own echoes—that wonders in loops how it wound up in an abandoned airplane hangar.

The editor in me is asking, “Is this essay really still centered on autism by the end, or did you just weave your way into an essay about mental health?” The answer is: Yes.

I couldn’t have written about one without writing about the other. It’s just how it unfolded for me. My depression, anxiety, and autism feed into one another. They always have, even when I didn’t know that I had any of them. Even if my parents had taken me to mental health professionals early and often and had worked diligently within the school system to see if there were some help that might have been available to me, it’s entirely possible that none of those avenues would have led to an earlier diagnosis of autism (or Asperger syndrome, given the time period).

Still, it would have been a beginning. Even if it hadn’t been obvious that my anxiety and depression were exacerbated by autism, my anxiety and depression would have been on full display in front of a professional who might actually have been able to help me with them. I might have made early first steps down a path of learning to cope with those things. At the very least, I would have been heard, and I likely would have been taught some practical skills to mitigate my sensory and attention issues. I might have received my ADHD diagnosis when I could have benefited the most from it. At present, if I close my eyes and imagine the alternate timeline where all of those things came to me early, I feel heartbroken that they didn’t. Maybe I won’t always feel that way.

I recognize that there’s not really a wrong to be righted by interrogating my parents or by calling them out. I can say, “They were doing the best they could,” if I’m mindful of the spirit of that saying. But working through this while it’s on my mind—particularly in writing—has been helpful to me insofar as I’ve been able to release a bit of ages-old tension. If shining a light on my parents’ parenting helps in that way, then I think it’s worth applying the scrutiny of a journalist. (I’m not a journalist, but I really dig their scrutiny.)

Writing is certainly more productive than ruminating on the same subject alone at night without an audience in mind. It’s also made me look more closely at my own parenting. Where can I cut myself some slack? Where shouldn’t I cut myself some slack? When do I need to hold myself accountable? What are the red flags that I might be fooling myself into thinking I’m protecting my kids when really I’m just too overwhelmed to acknowledge a problem by saying it out loud?

Stay tuned!

One nice thing about approaching this as a series? The end above isn’t really the end! So, thank you for your service, parents everywhere. Throw yourselves a parade. Next time? Professionals and institutions!

Final Note: This wasn’t intended as a scholarly essay, but in passing I say a lot of things that could benefit from a fact-checking department. Unfortunately, I do not have one of those. I did my best to verify my own claims, but if anyone reading has an “Um, actually…” moment, I encourage you to politely let me know, perhaps via DM. I will make any verifiable factual corrections and note any major edits here. This is primarily a personal piece, but I am loathe to spread misinformation—especially where mental health is concerned.